In Death's Dream Kingdom

Houndstooth 2018

In its young existence, Houndstooth has developed a penchant for

putting out music that feels ominously present. 2017 alone saw the release of

acclaimed full lengths by label auteurs Throwing Snow, Special Request, and

Call Super that tap-danced across electronic styles; each took ingenuous leaps

forward with an aura of timelessness, and displayed beauty, freedom, and

identity in strange sections of the minutiae. But the challenge faced by

current musicians and record companies alike is maintaining universality, while

staying mindful of the contexts that surround an ever-changing world around

them.

Within this organization, most have come to understand that facing

reality can be an unpleasant task. The averted closure of fabric, its parent

organization and prolific nightclub, in 2016 was a painful ordeal for artists,

fans, and figures behind the scenes whose painstaking efforts made their recent

flourishes possible. Sadly, the scare was far from the only existential threat

at play in this community and others over subsequent months of global turmoil

and unrest. At a time when serious doubts and fears linger in the air with

discomforting regularity, it should come as no shock that among this creative

cohort, the UK, and beyond, the quality of “present” music and art is as

important today as it ever has been.

With In Death’s Dream Kingdom, Houndstooth has seized the

opportunity to showcase its resiliency, artistry, and audacity, grabbing it by

the lapels and shaking loose twenty-five dreadfully gripping experimental

tracks by as many artists, managing more continuity than could possibly

be expected in such an unprecedented form. The project’s title, derived from

T.S. Eliot’s evocative The Hollow Men, is a fitting inspiration for a

collective so stylistically scattered and adept at using non-linear approaches

to develop synergy with their surroundings at large. To borrow Eliot’s words,

they oblige to occupy a space “between the potency and the existence/

between the essence and the descent.” Befallen to derelict places, the poem

extends an unsteady hand toward an intriguing if not insidious prospect for the

figures involved, not only in their placement alongside other compelling

artists on a beefed-up quasi-playlist, but also in drifting toward untrodden

realms of noise and sound.

After parsing the anticipation of its announcement, the slow tease

of its day-by-day releases, and its digital-only accessibility, the first

indication of IDDK’s ambition comes from the diversity in its list of

participants. A heterogeneous mixture sees masters of ambient, atmospheric

styles featured next to peers best known for convulsive techno or

unclassifiable avante-garde, and nearly everything in between. But if it seemed

like the stark intimacy of Pan Daijing’s sinister work couldn’t share space

with Bristol-based producers Hodge and Batu’s dub and bass, or that the

Shapednoise take on Eliot’s line “shape without form” couldn’t follow the

freakish energy harnessed by Gazelle Twin, their slick confluence will come as

a surprise. Time and again, songs adhere to one another in the shadows

(Spatial/ Yves De Mey) only to juke sporadically in jarring fits and starts, a

texture that dovetails the possibility of slipping into the background and

demanding full attention. The bulk and amalgamation are oddly functional in

this way, carefully avoiding the pitfalls of turning complacent or redundant,

despite serious volume.

But there’s more to the boldness of this array than its strange

pairings or its massive appetite; the essential component is the singularity of

its aesthetic. Creating sounds without limitation is liberating in theory, but

the possibilities can be daunting without requisite points of focus or

conceptual coherence. In this case, The Hollow Men is a five-part beacon

and constant reference point. Its unsavory suggestions (“This is the dead

land”) and overarching solemnity (“Quiet and meaningless/ As wind in dried

grass”) offer a creative foothold, and impervious imagery catalyzes wicked

chain reactions. Abul Mogard’s enveloping “Trembling with Tenderness” is IDDK’s

most emotive effort, latching onto Eliot’s vulnerability and imitating it with

deft touches and shifts of force. Later, it’s Roly Porter’s turn to give a

literal interpretation in an infectious rendition of “Without Form”, complete

with garbled swells of reckoning. The indirectness of the stanzas’ thick tones

works just fine, too, as clearly evidenced by Petit Singe and Sophia Loizou’s

mechanical entrenchment around harsher ideas, much in the same way the aqueous

environments of Tomoko Sauvage and Koenraad Ecker compliment the poem’s organic

material.

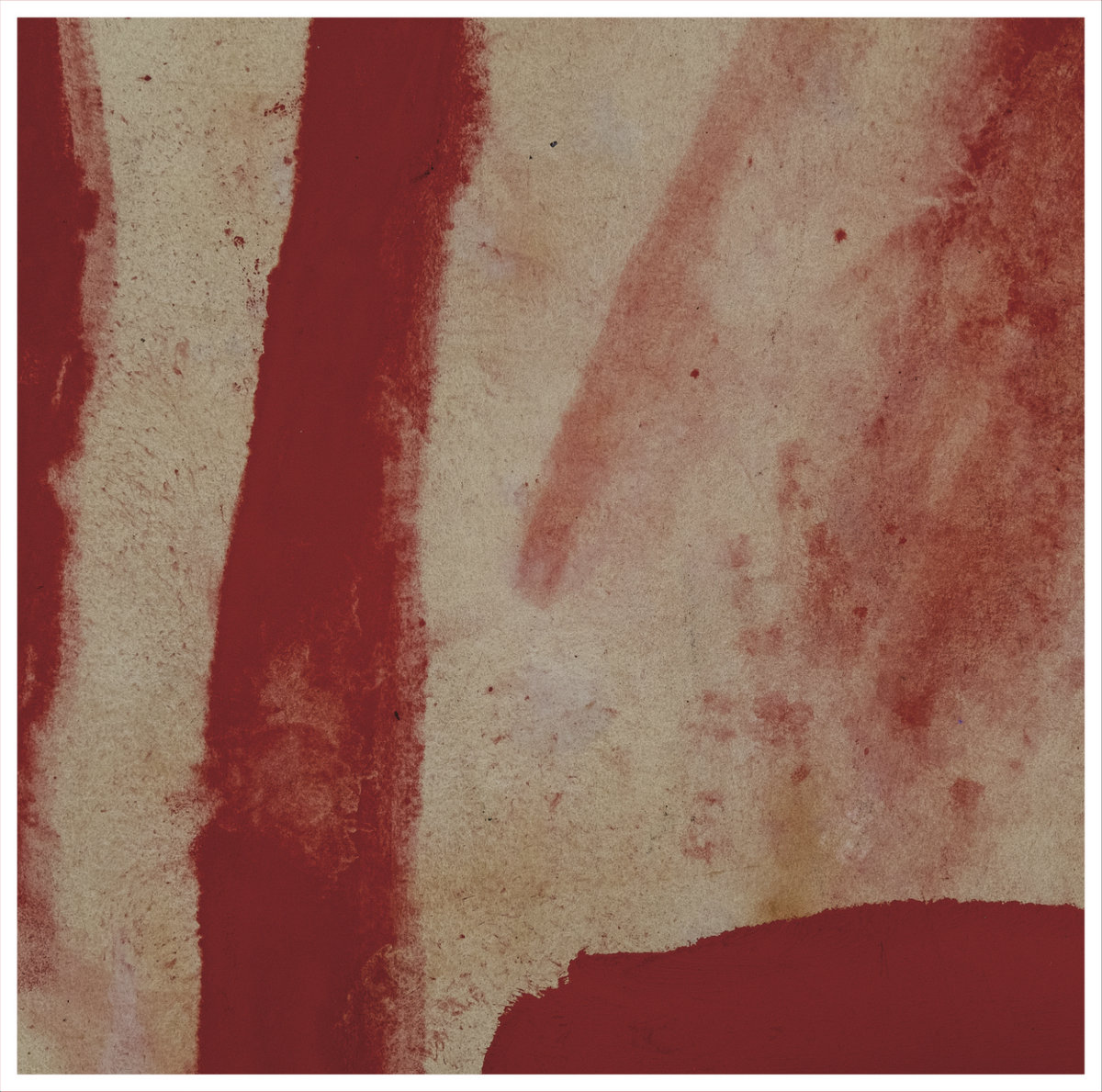

It’s the display in Jazz Szu-Ying Chen’s stunningly spare cover

graphic that aptly and bleakly brings the connectedness of the literature,

visuals and sound full circle. But, naturally, calibrations were needed to take

the musician’s familiar methods and align them with the cloudy timbres called

for in their prompt, where sensibilities are stripped skeletally bare, and an

opaque blanket of fog rife with despair obfuscates the escape from an empty

existence. For percussive techno producer Peter Van Hoesen, kick drums and four

on the floor basslines are set aside in favor of bellowing drones and sweeps,

creating what could be a soundtrack for a slow-motion collision of atoms.

Others use outbursts of brooding energy to leave Burial-esque dark vibrations

in the air; Pye Corner Audio’s “Box in a Box” churns along with heady

determination, while ASC’s effort “Tesselate” uses its cosmic underbelly to

reach for something more paranoid. Regardless of which tactic is employed, each

song is its own house of cards, threatening to turn in on itself or collapse at

the smallest provocation.

To be fair, ambition and curiosity aren’t exactly unprecedented

for those behind Houndstooth’s unique vision. Rob Butterworth and Rob Booth,

who in tandem run the label, have used their FABRICLIVE and Electronic

Exploration series, respectively, for over a decade to give chances for both

young and established musicians (including many that contributed tracks to

IDDK) to spread a rarified, abnormal lens to the outer reaches of DJs and

producers. Of equal significance, they’ve cultivated the symbiosis of community

readily apparent throughout these recordings and in previous compilations,

namely in the 111-take #SAVEFABRIC, which served as a precursor to their

undeterred approach to voluminous collections, particularly in the underground.

In Death’s Dream Kingdom embarks on a mission to

acknowledge the largess of streaming-era music consumption, but subvert the

impersonality of “everything now” information seeking and instant

gratification. Instead, at the core of its existence is a combination of sonic

exploration and external awareness as a powerfully redemptive force. Amidst all

of the boundary-pushing and aural shapeshifting are tracks comfortably adrift

in the waters of abstraction, yet grounded in Eliot’s disconsolate thematics

and bleak images. The dying energy of Ian William Craig’s sprawling “An End of

Rooms” adds finality and a necessary moment of pause. Wide-eyed, shaken, and

under the dim twinkle of a fading star, we’re left grappling with a compilation

rooted in a century-old poem and in reality, one that will surely wind up being

one of the most beautifully unsettling releases of the year.